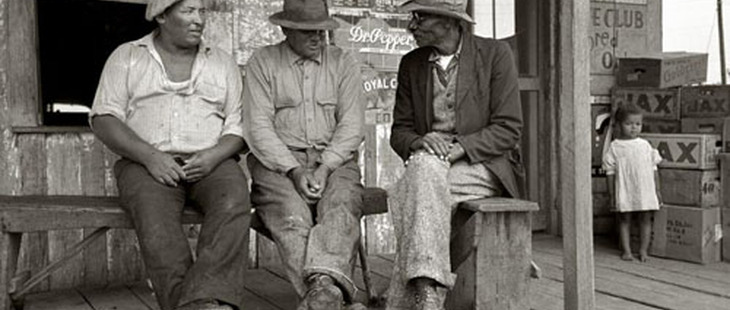

(Photo: Russell Lee, 1938, for the Works Progress Administration) Confession. I’m a trained historian, which in most cultural moments is a decidedly uncool profession. Except now I’ve noticed that our official uniform–tweed jackets, corduroys, and glasses–is “in.” Another problem with being a historian is that, generally, we are obsessed with the past. So when a company suddenly discovers its “heritage” and the fashion-conscious start wearing clothes first designed in the 1930s, I have another problem. I can dress like my historical protagonists! This has been good for L.L. Bean Signature and Red Wing but decidedly bad for a graduate student’s bottom line. There is one final problem though. Doing what I do I can’t help but analyze things with a connection to the past. As someone who studies and teaches African American and cultural history, I’ve noticed that there is something missing in fashion’s celebration of the past. During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dispatched a bunch of artists and photographers under the aegis of New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration and Farm Security Administration to capture the “essence” of America. Instead of working as waiters and baristas, as they do today, these men and women travelled America writing plays, taking photographs, painting murals, and generally celebrating the country on the government’s dime. With capitalism in crisis and communism on the rise, FDR was worried that American workers would demand a fundamental shift in American economics. As a result, these artists–themselves often sympathetic to organized labour–created a romantic image of work that helped get America’s workers on the New Deal side. These artists were part of a cultural front that recast the American worker as icon. With a few exceptions they also, unfortunately, made the idealized American worker male and white. The great tragedy of FDR’s project was the way in which people of colour and women were largely excluded from the American celebration of work. Before the economic collapse of 1929, many native-born Americans did not consider recent immigrants to be fully “white.” However, with the expansion of New Deal agencies and unions into the fabric of American life, coinciding with the emergence of a mass culture facilitated by the radio and cinema, old ethnic allegiances faded and the definition of “whiteness” expanded. By the end of the 1930s, Italians, Poles, Hungarians, and Russians were no longer viewed as separate races but lumped together with people of British descent as “white.” New Deal cultural workers tapped into this expanded conception of whiteness when they celebrated the American worker, but largely left African Americans, Hispanics, and women on the outside looking in. Although some of the most iconic images captured during the initiative were of women or African Americans, such as Dorothea Lange’s famed Migrant Mother, by the onset of the World War II the popular image of the American worker was white and male. Migrant Mother, 1936, by Dorothea Lange The legacy of this has been felt throughout the twentieth century: American unions have fought against the inclusion of women and African Americans, Reagan decimated the labour movement by playing on the fears and anxieties of white workers. Three decades later and the image of the white male as the quintessential worker has largely stayed with us. Fast forward to the Great Recession. Like the last great calamity in capitalism, the blue collar worker or farm hand persists as a romantic cultural emblem. One needs only to head down to Queen West to see young “working-class” men heading to grab a latt before buying the latest in “heritage” gear. And don’t get me wrong; I’m a fan of the trend. I look for made-in-America (a little more made in Canada would be nice). But there’s also something troubling. While looking to the quintessential American worker for inspiration, fashion brands from the Gap and J. Crew to more high-end labels like Woolrich Woolen Mills have yet to update their image to reflect the true colours of the American worker. Take some time to go through the many blogs devoted to heritage fashion, such as Vintage Workwear, The Sporting Life, The Art of Manliness, or A Continuous Lean, and it’s clear that today’s men’s fashion has once again erased the African American, Hispanic, and female workers of the past. Looking at these websites it’s clear whose heritage is being celebrated. Absent is the “heritage” of American racism, which has erased the heterogeneity of the nation for a distinctly homogenous one. These bloggers and designers don’t realize it but the image of “heritage” and “authentic” they appropriate is a small slice of historical reality. Heritage and authenticity are highly constructed, historically contingent concepts. In the 1930s African American labourers and female sweatshop workers were left outside the celebrated image of work. While white “gentlemen farmers” became a symbol of the heartland, black sharecroppers and Mexican agricultural workers attempted to scratch out a precarious existence. And they all wore Levis. The extension of this fashion trend has been the ongoing celebration of American blue-collar or agricultural workers, who should be given their due. These were the men and women who built America and fought for freedom, becoming part of what we now know as the “Greatest Generation.” They were also a generation that was a product of an incredibly insidious racial system. The racial and gendered divisions in the conception of work that hardened during the Depression have had a devastating impact on the labour movement and American society. Despite the gains of the civil-rights and feminist movements, notions and images of “hard-working” Americans too often remain overwhelmingly white and male. So when we buy our Carhartt jackets to go over our Gant Rugger sweaters, let’s remember the erasures that have taken place. More than anyone, minority groups in America have done the down and dirty work. If we celebrate the American worker, or a romantic image thereof, let’s have an inclusive vision. A vision that will make space for not only industrial workers but farmers, migrant labourers, and all those who put in an honest day to pay the rent. In doing so, we may take a tentative and no doubt small step in escaping the legacies of race in our supposedly “post-racial society.” __ Nathan Cardon is a Ph.D. candidate in History at the University of Toronto.