Ronald Firbank

Text/Book, the Toronto Standard‘s books column, is written by Emily M. Keeler and Chris Randle, plus occasional guests.

Recently, in a single gluttonous week, I read several novels by the long-dead, semi-obscure English author Ronald Firbank. My introduction to his writing was ostensibly research for an article, but it didn’t feel like work, perhaps because it never felt like a traditional narrative either. Psychological probing was meaningless for Firbank, plot development an intermittent nuisance. In books like The Flower Beneath the Foot he created realms of camp decadence, where stylized characters carry on absurd conversations amidst chameleonic sexuality. Despite the pervasive hormonal haze — as a parenthetical from Sorrow in Sunlight asks, “what wild follies were not committed in shuttered-villas during the throbbing hours of noon?” — responding to it rarely seems very pressing. Firbank made frivolity his catechism.

In this, as in many other ways, he dealt with a form of misdirection. Born in 1886, the grandson of a Durham coal miner who found wealth through railway work, Firbank enjoyed a great inheritance, at least theoretically — by the time his MP father died the fortune was heavily depleted, leaving only enough to liberate him from conventional employment. Effete, sickly, restlessly cosmopolitan, prone to spindly spasms and outbursts of hysterical laughter, his extravagant awkwardness imparted a mordant understanding of thwarted disappointment. It appears that his attraction to other men seldom became physical. His books were published at his own expense, not inspiring scandal so much as distaste. Firbank converted to Catholicism in 1907, undoubtedly sating a taste for gaudy ritual, but his efforts to join the Guardia Nobile all failed. He later wrote to a friend: “The Church of Rome wouldn’t have me and so I laugh at her.”

The Church had company. Ruthlessly pared of excess text, Firbank’s prose sometimes comprises little more than witty, Wildean dialogue. In The Flower Beneath the Foot‘s Kairoulla (a bizarre Viennese-Arabian melange) courtiers, aristocrats and nuns speak fragments of unsuccessfully suppressed lust: “I would not care to scathe your ears, my Innocent, by an inventory of one half of the wantonness that went on”; “Where I reign, shyness is a quality which is entirely unknown”; “Once, men (those procurers of delights) engaged me utterly…I was their slave…Now…One does not burn one’s fingers twice, Mrs. Bedley.” Middle-aged ladies withdraw camp titles like The Beard Throughout the Ages and Men Are Animals from the local library. The novelist Alan Hollinghurst, a devout Firbankian, has ascribed “a sort of emotional transvestism” to him, and argued that the feminine perspective of his later books “becomes more obviously a sly means of expressing his own homosexuality.”

Idiosyncratic as it may have been, Firbank’s amused, ecumenical queerness makes sense to me; I’m not so nomadic, but I have joined his fellow travelers. One of those “cult writers” whose sect isn’t quite influential enough to keep most of their idol’s works in print, he’s nonetheless turned numerous authors into fans. Harry Mathews once called him “probably the inventor of modernism in English,” adding that he “perfected the disjunction between surface and substance, between what you’re reading and what’s actually going on.” He cultivated Kairoulla’s baroque, face-fanning atmosphere through radical reduction: “I think nothing of filing fifty pages down to make a brief, crisp paragraph, or even a row of dots.” Yet standard accounts of literary modernism often marginalize him as an eccentric diversion, and it’s easy to comprehend why. Evelyn Waugh, a former admirer, told the Paris Review that there must be something wrong with an “elderly man” who could enjoy Firbank. I’m reminded of a line from his scorned target’s Valmouth: “None but those whose courage is unquestionable can venture to be effeminate.”

Where Waugh sneered in derision, Hollinghurst eventually paid homage. Snatches and images of Firbank flicker through The Swimming-Pool Library, his debut novel. The protagonist becomes an avid convert, reading Valmouth and all the others; one vintage edition even gets stomped back into pulp by some homophobic skinheads, a flower, as it were, beneath a foot. During the final pages Firbank makes a personal cameo, near Lake Nemi and near death, on a sliver of film: “This marionette of a man, on his last legs, had been picked on by the crowd, yet as they mobbed him they seemed somehow to be celebrating him. He became perhaps for a moment, what he must always have wanted to be, an entertainer. The children’s expressions showed that profoundly true, unthinking mixture of cruelty and affection. There was fear in their mockery, yet the figure at the heart of their charivari took on the likeness not only of a clown, but of a patron saint.”

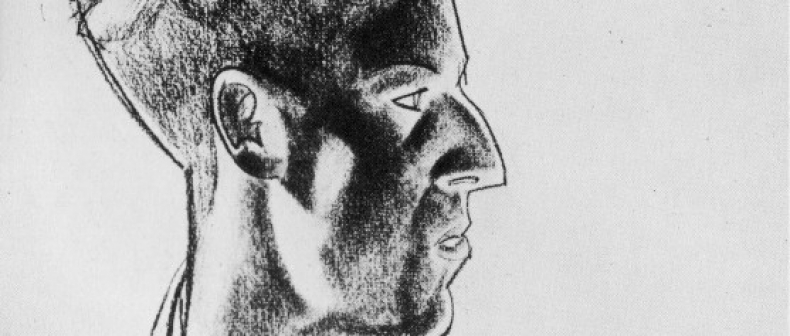

Hollinghurst would later write that his predecessor specialized in comic characters with tragic destinies. That fascinates me too — I’ve been using Firbank’s impassive, bow-tied, obliquely louche portrait as my Twitter avatar — but there’s a limit to how close my identification can be. Despite a few similar biographical details on the paternal side of our backgrounds, I’m agnostic/disinterested, drawing privileged breath through working lungs, and straight, however feyly. My friend Sholem Krishtalka has suggested that “queer” should be seen as an aesthetic, a sensibility or an ethos, not just a question of whom one sleeps with. As much as that notion appeals to me, there are queer areas of lived experience that can’t be universalized.

Some years ago I saw a Trampoline Hall lecture by the local writer Derek McCormack, whose extreme minimalism and nose for tragicomedy recall fabulous dead Ronald. It focused on vintage novelty gags, a fixation of his, and his thesis was as elegant as a syllogism: “Gags are gay, because being gay is a gag.” Maybe so, but it’s not my place to say. I will never be the punchline.

____

Chris Randle is the culture editor at Toronto Standard. His favourite Firbank coinage is “concertinaishness.” Follow him on Twitter at @randlechris.

For more, follow us on Twitter at @TorontoStandard, and subscribe to our newsletter.