I have seen noon, but I haven’t yet seen midnight. I’m planning to see midnight, in fact I’m eager to see it; but you can’t see it all the time — only every other weekend. I’ll be able to see midnight this weekend.

I’m referring, of course, to Christian Marclay’s The Clock, a 24-hour video installation currently on view at the Power Plant. Marclay has created, out of film and television clips, a fully functional 24-hour clock. Most of the time, the gallery is keeping its regular hours — from 10 am to 5 pm — so you can only see The Clock run through those hours. But every other weekend (including this upcoming one, which coincides with the Nuit Blanche festival), the gallery opens its doors for 24 hours, and you can see The Clock run through its full cycle. If you have the stamina, that is.

I am willing to say, for the record, that The Clock is one of the most important artworks of its kind, if not its time (no pun intended). The above one-line description will never do it proper justice, and any review will only do it partial justice. The conceit seems simple enough, but the experience of it is a profound thing; Marclay is doing nothing less than completely dismantling your experience of time. Sure, at a very basic level, you’re watching nothing more than a clock tick. But The Clock is so much more than that; you are watching people experiencing time, through the particular filter of the mythic dimension of cinema, with all that that implies in terms of identification and empathy. The absorption and processing of this installation unfolds slowly, second by second, minute by minute, hour by hour, and each tick of the second hand unveils a new layer of altered perception. And just as everyone experiences time differently, everyone will have a different experience of The Clock.

It’s an odd thing, spending hours watching people on screen check their watches. The Clock presents a universe of people mercilessly ruled by the implacable procession of digits that mark where they are, where they should be, and where they aren’t. It’s a universe that dances to the steady, perpetual beat of the second hand, and we are enslaved to that grim music, like the exhausted marathoners in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

Cinematic time is different from mundane, lived time. For one thing, most films unfold in a more-or-less standard two-hour period, which, most often, encompasses days, months, years, sometimes decades, a narrative alteration that we largely take for granted. But even films that unfold in “real time” — Cléo de 5 Ã 7, for instance — are structured around the ebb and flow of dramatic narrative: an accretion of significant events that builds towards climax, resolution and dénouement. Your watch has no such responsibilities. And so one of the most immediate rewards of The Clock is how fundamentally it alters the passage of time. On a pragmatic level, it’s marking the passage of minutes. But it is doing so via the filter of cinematic time, and so every moment is building towards something, and some hours fly easily and gracefully, and others are marked by a ritualistic, monumental significance.

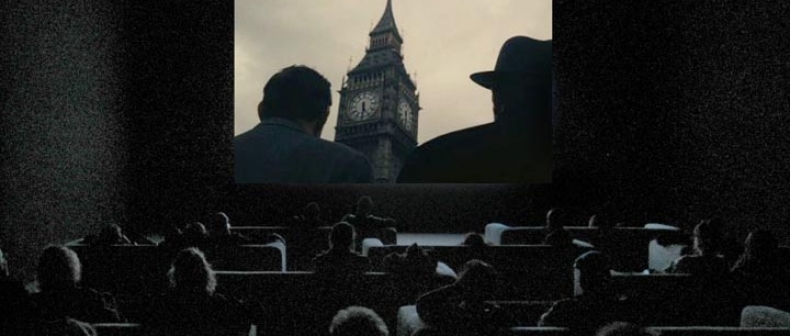

The first time I saw The Clock, at the National Gallery of Canada, I watched it from 6:30 to 7:30 — characters were getting off work, meeting each other for dinner, watching the sunset. No great crises. But then I watched it from 11:30 to 1:30. For the first half-hour, the strike of noon was a terrifying imminence: cowboys loading their guns, nervously watching the sun; men in suits frantically glancing from clock to phone and back again; men climbing Big Ben, trying desperately to hold on to the outsized minute hand as it makes its implacable voyage towards verticality. The stretch from 11:55 to noon was an extended miasma of anxiety that seemed to stretch on for hours. Time pressed on nervously, trepidatiously, urgently, until the hour struck and all hell broke loose: guns were fired, bombs exploded, hunchbacks rang bells in a gleeful fury. And then, just as suddenly, the crisis abated: at 12:05, lovers woke too late from their sleepy idylls to the harsh light of consequence; lunches were being prepared; trains arrived and departed. And before I knew it, the easy rhythm of midday flew by and it was 1:00 and Richard Gere had to take a phone call.

______

Sholem Krishtalka is the Toronto Standard’s art critic.

For more, follow us on Twitter @TorontoStandard and subscribe to our newsletter.