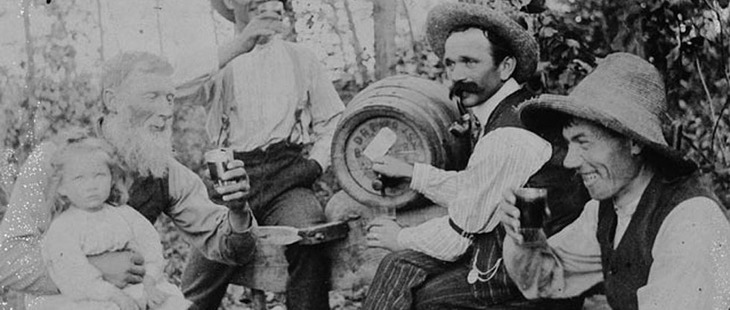

(National Archives of Canada) (Read Whiskytown Part I, here.) What whisky made, beer tore apart. For decades Toronto was the world capital of whisky. Gooderham and Worts, the planet’s largest producer of spirits, occupied a massive industrial complex at the base of the Don River. Their demand for wheat developed Ontario’s farm industry while their international shipments opened new global trade lines. In Italy, all roads led to Rome; in Ontario, all rail lines led to the distillery. Yet, for all of its success and all of its power, Toronto’s whisky-opoly was a dead man walking from the moment it came into existence: above all else, even its spirits, it produced its own gravediggers. The global reach and the business success that Gooderham had achieved at its zenith owed its foundation to the early, pre-industrial Canadian economy. Farm hands and canal labourers had a virtually insatiable thirst for whisky: it took the edge off of their work, it was valuable, and it was a lot more fun than the only alternative: water (milk, tea and coffee were not yet so widely available in Canada). But while demand was significant, supply was haphazard. Produced in mills across the province, the volume of whisky available for sale each year depended on the whims of the individual distiller. Their primary business was flour and the decision to divert energy and raw material to spirits depended on an economic calculus comparing the global price for wheat to the local one for rye. The genius of Gooderham was to mass-produce, in a regimented and productive way, explicitly for this demand. In this, his company was a harbinger for two related economic trends: the rise of a domestic consumer-goods economy and the birth of the working class. It seems inevitable now, but for much of the 19th century no one really thought that Canada could, or should, develop an industrial economy. Why not be the breadbasket for the world, the last refuge for the manly farmer? What point was there in making things in Canada for Canadians? The mills of Birmingham, the shops of London could surely furnish the small population with whatever it required. Gooderham proved, perhaps unknowingly, this theory to be wrong. Perhaps the Canadian economy and nation could have continued without development, and without the comparative luxury of the colonial heartland, but Canadians (particularly the rich ones) were no more immune to the capitalist, developmental impulse than their cousins in England or America. Still, no one really noticed the significance of Gooderham opening a whisky factory (no one could really fathom Canada as an industrial power). Nor did he notice the effect his workers, and their brethren, were having on his business. While Gooderham and Worts was the first, it was not the last company to open a factory in Toronto. More and more began to set up shops and, with them, more and more workers moved to Toronto. Throughout the 1800s the urban population of Canada grew by six percent each decade. And they drank, but they drank differently. In rural Canada, when whisky first became popular, it was not uncommon to drink on the job, on the way home, at home, at the tavern, with friends. That is, it was not uncommon to drink whenever you wanted to. Factory labour and working-class life, however, had an entirely different rhythm. While working for ten to 12 hours a day underneath the eye of a foreman, drinking on the job became an activity increasingly frowned upon. A new work ethic developed: socializing on the factory floor was forbidden; one’s attention had to be singularly focused on the work at hand. Leisure time and work time suddenly became demarcated. And just as rural and urban life were organized differently, the alcohol best suited for each life was different. Beer became the choice drink for the urban worker. One of the main benefits of spirits for the rural labourer – that you could keep it in a flask and bring it with you – meant nothing to the urban worker. The latter’s choice of beverage was a practical choice. In an age before the beer bottle or the hermetically sealed can, it was impossible to keep or transport beer. One brewed it and sold it right away. In the city a brewers’ economy developed along lines reminiscent of the original whisky economy: independent proprietors produced for the local market. Operating on a small enough scale they escaped the notice of the tax collector and were thus able to provide a cheaper product than Gooderham and Worts. Losing the market of the poor hurt Gooderham and Worts, but the deathblow came with middle-class moralism. Riffing off the industrial Protestant work ethic, a teetotalling campaign gathered momentum in the second half of the 19th century and into the 20th. Noting the incompatibility between intoxication and a rigid regular work life (not to mention Christian family mores), a class of activists sought to ban the sale of alcohol in both Canada and the United States. Reaching a climax in 1910s, community after community, and neighbourhood after neighbourhood, slowly opted-in to prohibition. Increasingly the trade of spirits was conducted on the black market. But worse, for Gooderham, they had grossly misunderstood the direction of the market. Whisky was no longer the drink of the poor by the time of prohibition; exiled from working-class communities it had been adopted by the rich. Brands like the competitor Canadian Club flourished as orders came in from the United States asking for the more respectable drink. Gooderham was trapped: its original market gone, the new one perceived its product as inferior. In 1926, Gooderham was merged with Canadian Club and the company ceased to exist. The city, however, has not seen it fit to forget. In a perverse kind of tribute, there is now a craft brewery, Mill Street, on the site of Gooderham’s old factory, the now refurbished Distillery District.