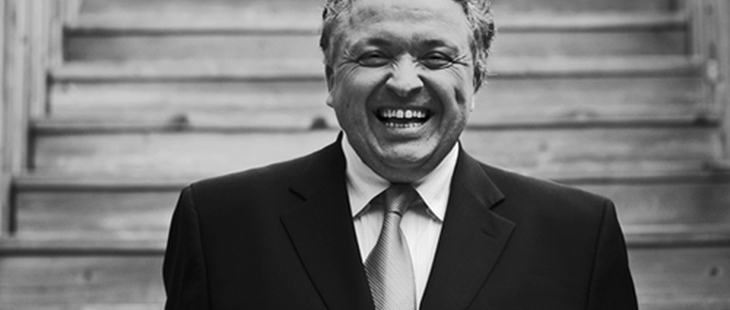

Bruce Mau cares less about “the world of design,” but rather something like “designing the world.” He’s been called a global visionary, an innovation guru, and a smasher of genres. Yet he prefers, simply, “designer.” He’s multilingual in more mediums than most can imagine: visual identity, book design, interdisciplinary art exhibitions, public space projects, and post-graduate studio programs. His studio Bruce Mau Design has worked with clients including Coca-Cola, MTV, Indigo Books, as well as noted icons such as Herman Miller, Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas. Mau is the brain behind such broad-but-bold initiatives as the widely-recognized Massive Change project exploring the future of global design and the Institute without Boundaries at George Brown College.

He’s a Toronto institution, even if he now makes his home in Chicago. Tomorrow night he’ll be speaking at the PEN Canada International Festival of Authors Benefit, of which the Standard is a happy sponsor. We caught up with Mau just before he left his Chicago studio.

First, what’s this all about—you, a designer, giving a talk as part of the PEN Canada Benefit at an author’s festival?

I’m a little uncomfortable being perceived as an author, and not a designer. So I was going to address the similarities and differences between them: what authors do, what designers do. And try and prevent myself from being measured as an author, because I think I can never attain the impossible standards that authors meet. Part of this is looking at what are the common threads in the ways that we think and work as authors and designers.

But you have authored books, like Life Style (Phaidon), and you’ve been one of the more eloquent exponents out there in terms of what design can accomplish outside of its traditional parameters.

I’ve tried to make the journey back and forth. But I have this image… I’m standing on a bridge, looking down on two trains that are travelling on two tracks, side-by-side. If you look at it as a still image, it looks easy to jump from one back to the other. As a moving image: you realize that the trains are actually moving in opposite directions and jumping from one to another, you can really get hurt.

If you think about the economies of being an author or being a designer, they are moving in opposite directions. An author tells the truth and a designer invents the truth. An author is going to push what they are doing out in the world, no matter what. Come hell or high water, the author is going to push that into the world because they have to do it. Whereas when I see hell or high water, I am fine. (Laughs) I think, great. “Come hell or high water,” I say, “we’re good.” I’m not going to do anything, unless someone asks me to do it.

As a designer, you only respond to problems that someone else has invented. I have a joke with my wife, who works with me, that I would do nothing, absolutely nothing, if I could. If left to my own devices, I am not going to do anything.

Designers are extremely lazy.

We’ll challenge you slightly on that. There are these things called the Institute Without Borders and Massive Change, which as far as we know, no one necessarily asked you to do.

I have great friends who are artists. They basically set up a client for themselves, in order to do their work. They set up a deadline, a delivery, and a commitment that really is the domain of a designer, in order so that they feel compelled to produce the work that they know they want to do. So they sort of set up a fake design economy to do their author economy. I know that in my own case that there are certain things that I want to do, that I have to do projects in order to explore the things that I’m interested in. I find a kind of authorship in it.

The Institute without Boundaries and Massive Change were both commissions. The Vancouver Art Gallery came to me and said here is a major project on the future of design. I said, “Oh, really?” At first I didn’t want to do it, it seemed really hard. And George Brown College came to me and said we want you to design some educational innovation [programme]. So I basically said, “Look, here is what I want to do, and I’ll illustrate a thoughtful way we can do it.” To my surprise they said, “How fast can you do it?”

But most of my work is produced in this other economy. People call me and say, “Could you do a Museum of Biodiversity.” You have no idea what that is and I have to figure that out. That’s what I am going to talk about a little bit about [tomorrow night].

The current Occupy Wall Street movement and its off-shots had us thinking about your project in Guatemala a few years ago. Essentially you were asked to design a sort of social movement, an initiative to raise awareness of the country’s potential, to elevate its sense of self after decades of civil war. Based on that experience, and Institute without Boundaries, and Massive Change… what have you learned about social change, and what organizations can do to construct a movement?

That’s a really good question. We learned quite a lot [in Guatemala], I’d never done anything like that. Basically a lot of our work, what we’re doing every day, is convincing people that there is a better way. And what you realize is that, if there’s a way of defining design in this super diverse practice it is really about leadership.

If you ask “What is design?”, it is imagining a future and then systematically working to execute that future. So whether that future is a product, social change, a new experience, a new way of doing things, that methodology applies.

I went to Guatemala and thought, “Wow, I never imagined doing stuff like this.” I never imagined I’d be called on to do deal with the fact that a society has lots its capacity to imagine a positive future. After 36 years of civil war, its imagination was dominated by extreme images: violence, poverty and corruption. We needed to systematically invent a new image, a new capacity.

I learned a lot about my own culture while in Guatemala, that we have so many foundations to build upon, that we take for granted. We take for granted that there’s a culture of justice, a culture of education, a culture of entrepreneurship and innovation, there is a culture of collaboration and openness.

When I was in Guatemala I was accused of being right-wing. I was accused at one point of being the CIA. I had to say, “But I’m Canadian! We don’t have a right wing. All of our birds fly in circles, they only have left wings.” It was surprising to be characterized in that way, but it was because I was working with businesses. Because I was working with entrepreneurs, I was labeled right-wing.

So we created a foundation to build upon, what we ended up calling “Culture of Life.” Because there you have these crippling polarizations. It’s one of the challenges, people just don’t work with one another. It’s an incredibly daunting task.

Page 2 of 2

To address another daunting task… the future and sustainability of cities. You’ve looked at urbanism a lot over the years, and more recently considering what we do about the suburbs. I’m of the mind that obviously they’re here to stay, and that we have to get beyond the idea of complaining about them. Instead we should consider them an asset, or a resource to work with and redesign for the future. So here’s an open question… What’s your general attitude about the suburbs?

It is interesting that you framed it that way, because I’m in agreement with you. I think most people look at an urban context and think of it as static and perpetual. In other words, if it’s a suburb now, it’s always going to be a suburb. If you think about what makes a suburb problematic, it’s basically two things: cars and the lack of complex infrastructure—in other words, something more than sleeping quarters.

So if the car is a problem we solve, which is starting to happen already, it’s no longer polluting, if we create new forms of public transportation and liberate people from the need to go to the city all the time, and we develop more complex infrastructure locally… it starts to mitigate the problems that you have.

It’s one of the urban great challenges we have, because we have huge amounts of this stuff. But I also think that it’s not so hard to fix. Because the existing infrastructure is quite modest, having to add stuff to suburbs wouldn’t be a big deal. Whereas to fix and already intensified infrastructure is much more challenging.

In the Toronto context, a couple things come to mind. We forget that neighbourhoods like Parkdale and Cabbagetown were once suburbs. Then we have this concentration of inner-suburban highrises, mostly built in the 60’s and 70’s that did create some density in the suburbs. Although they’ve reached a certain point in their lifespan and need an upgrade, these highrises are to Toronto, and a tremendous asset.

It is. If you look at the difference between Chicago and Toronto, Toronto is much more intelligent in distributing density around infrastructure. The beauty of Chicago is that we don’t do that. (Laughs). The beauty of Chicago is that we put all the density in the core, it is very dense, very dramatic and beautiful. You get the feeling that you are in a big city. But when you get on a tower and look out on the horizon, it’s basically two or three stories high as far as the eye can see. There are very few high rises.

We live in a suburb north of Chicago that’s extremely beautiful and designed by Daniel Burnham, but we have the train system that goes along the North Shore and there are single family houses right next to it, there is no density built on the line. If you look up the North Shore from an airplane, you can’t tell where the infrastructure is. Whereas in Toronto you can see it as clear as day. You can see every subway stop has density built around it, which is so much more efficient and intelligent. What you lack is the drama of the big city. But I think at some point you are going to get both.

I mentioned this earlier, people look at this as a static image. The fact is they are evolving conditions; they change much more quickly than we imagine. With a minimal amount of change in the suburbs, life there could be really wonderful. It wouldn’t take a lot.

You’ve pointed out that we’ve had great success in designing cars, thereby hooking us on this idea of individual mobility, but we’re not really applying the same lessons to public transportation.

The insight that I had was in Toronto in the wintertime. I was in the car with my wife, we have three girls so we had a mini-van; we’re in the car and we pull up next to a bus shelter in February. I looked into the bus shelter, there’s a women in there huddled in the cold, it was about minus 20 degrees.

I turn to my wife and say, “I know all about climate change and that stuff, but in a million years I am not getting out of the car. I am not going into that glass box.” Which is the same glass box that they use [at bus stops] in California. That tells you something about how poorly it’s designed. When you design it to lose, don’t expect it to win.

If you design to lose, you will lose. And at the moment we design transit to lose. It is a big fat loser and everyone knows it. When we say [the TTC is] “The Better Way,” what we should really say is “You really have no other choice.” Because that’s how it’s been designed.

When we design an experience that’s going to be bad, we’re surprised when people don’t choose it. If we want to we win we have to design to win. If we design an awful experience people won’t choose to use it. Then we say, “People won’t choose this over their car with 17 cupholders and Vivaldi.” When I look at that as a designer, I think it’s a great opportunity. We’ve succeed with the car and we need to apply the same level of design innovation to mass transit.