For those of us who grew up on a steady diet of text, the image-heavy nature of the web can sometimes feel alienating or just plain weird. Beyond the sheer glut of pictures pouring from our screens, as a Twitter friend said the other day, it sometimes feels “like the internet is trying to declare war on context.”

Now, Pinterest, the latest new web thing to catch everyone’s attention, seems to have taken the trend to its logical conclusion. The site, on which users simply “pin” images they want to save and share, prioritizes the visual over words; the mass over the solitary, considered object; the fetish over the analysis. Few things capture this fact more than Pinterest’s use of “infinite scrolling,” the term used for sites that automatically load more stuff as you move down the page. If you could once argue that Tumblr and its network-y, half social/half blogging schtick was the very paragon of the web, its Pinterest that now occupies that spot.

That unending stream of unexplained images is the kind of thing that French postmodernist philosophers warned would be the downfall of 21st century society. The rise of the image, richocheting around the public sphere, would rob them of context, and turn them all into free-floating, meaningless ephemera. It’s that phenomenon which would allow the Gulf Wars to seem like video games or celebrity news to overshadow geopolitics.

But it’s a stance that has become more difficult to maintain with the mainstreaming of the internet. The critique of the sea of images was always that, without accompanying explanation, it would all be a nihilistic mass. But the web constantly works to foreground context. We are constantly bombarded with explanations, ideas, opinions and new facts. We already arrive at images so overloaded with context that an explanatory frame is often unecessary. One could flash an image of Lana Del Rey for half a second and it’s likely ten ideas and opinions would pop into your head, almost against your will.

The age of the image is the age of the network. If in the print era we relied upon a linear relationship between one idea and explanations, in a networked society, the previously hidden connections between things are all around us, all the time. All hail the image, we can say now, because it is impossible for the image to remain untouched and pure. It arrives pre-explained, pre-determined by ever-so-much parsing and social baggage.

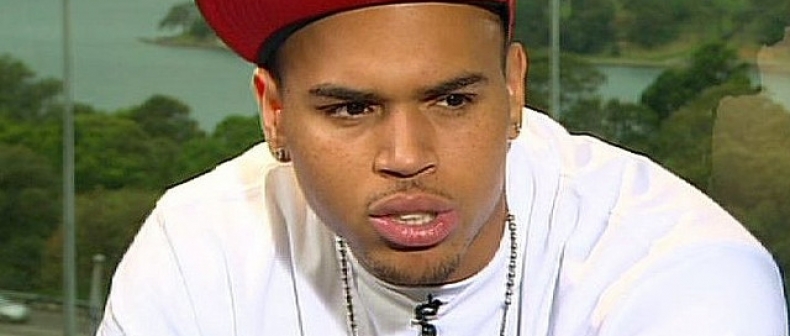

What complicates that view of the “precession of context”–the idea that context is so omnipresent, that it’s built a kind of “pre-interpretive frame”–is, oh, let’s say, when women watching the Grammys suggest they want Chris Brown to beat them.

Statements to that effect were collected by Buzzfeed this past weekend. The defense of those making the statements was largely that they were making a joke. If they were, it would ostensibly be the sort of humour that, uh, “works” because it’s already implied that violence is wrong. “Who might take a statement like that as anything other than a joke,” one might say, “when we all know that, in reality, it’s a totally unacceptable thing to say?”

I am increasingly a fan of the sort of transgressive humour full of faux-self-loathing that has emerged on Twitter. There’s a grit to it I think is necessary. But a tweet that says “Chris Brown can hit me”? It’s hard to see it as anything but wrong, offensive and courageously oblivious to how common, serious and pervasive violence against women is. And, as if it weren’t bad enough that Brown was on the Grammy’s at all, here were women making light of his abusive, violent past – and even implicating themselves in it.

If the free floating nature of 21st century ideas has divorced individual moments from context, the dangerous flipside of the situation is that things that are, by any measure, grossly wrong can seem okay. The history of images and langauge gets lost in a sea of alternate interpretations or no interpretation at all. University kids dress up in blackface. People talk of the end of racism and sexism. The market is only the choice for decent societies.

The urge of course, is the same urge as those lamenting the loss of print, or religion: if only we could get the good thing back. It’s a false hope and an unhelpful one, though. We can’t untangle history or undo the web. Pinterest, in literal or metaphorical form, is here to stay. But that’s not to say it’s a losing battle.

I was reminded of this recently when, amidst the Pinterest-hype and Grammy snark all over Twitter, I read a blog post called “Laughing and Crying” by Emily Gould. Of course, how does one hear the name “Emily Gould” and not think of the clusterfuck of reaction and discussion from her time at Gawker and front page story in the New York Times? It’s context, asserting itself again. It’s a terrible shame, too, because people have forgotten what a brilliant writer Gould is, and this latest piece is an exemplar of why. In many ways, Gould’s post is an essay on what it means to be a woman writing online, but it’s also about this precession of context. Most prominently, Gould relates her own passionate defence of how a simple collection of images of “women laughing alone at salad” betrays so much about our current moment. It contrasts that with Gould’s first experience of Lana Del Rey’s “Video Games,” which she manages to hear before the absurd scrutiny that has since been heaped on the singer, finding meaning where others later found only scorn.

It is these two ends that represent the problem with a Pinterest-ified world. On the one hand, a torrent of images and ideas robbed of context can produce a world devoid of history, where jokes about Chris Brown’s heinously unreprentant past are fair game. At the same time, breaking them out of the familiar can help us reconsider them or see them anew. It’s the tension between our need to remember history and our desire to be free of it.

Gould’s essay ends with her at a museum, crying tears of two sorts: first of sadness, suddenly moved while standing at the centre of an art installation which reproduces of the clear sound of 40 singing voices; and then of happiness, after a realization that the only way to fight other’s insistence on their own interpretations is to simply let go of a need to please them. It is a passage from having the familiar made new to an epiphany of what must be changed in the here and now–from temporarily being pushed out of history so that you can do something useful upon your reinsertion into the stream.

It’s seems a good a model as any we have. You fight when it’s worth it, and sometimes you just let go. Chris Brown jokes are a reason to fight. Born to Die seems like a reason to let go. And in the middle is life, in all its entangled, overdetermined mess.

____

Navneet Alang is Toronto Standard’s tech critic. Follow him on Twitter at @navalang.

For more, follow us on Twitter at @torontostandard, and subscribe to our newsletter.