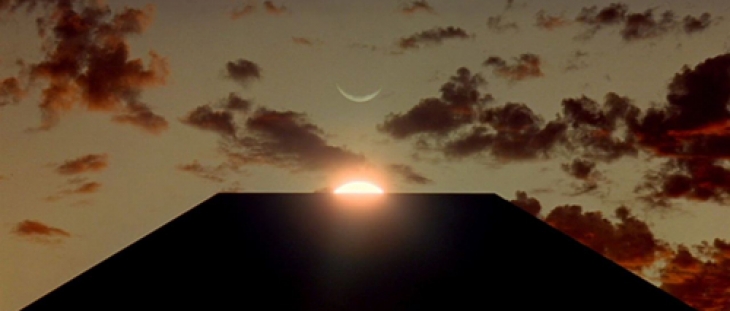

If the historical worth of a film is judged entirely by how often it’s parodied and referenced in pop culture, then 2001: A Space Odyssey is topped only by Star Wars and The Godfather as the most important cinematic work of the 20th century. Stanley Kubrick’s extraordinary science fiction vision is easily one of the most quoted and copied films ever: it’s a groundbreaking spectacle that rescued the science fiction genre from B-movie obscurity; irrevocably changed the possibilities and importance of special effects; and brought the slow-moving, high-minded aesthetic of 60s European art films to Hollywood. Technically awe-inspiring and thematically confounding, it’s also equally one of the most loved and hated movie masterpieces around. It’s a film both easy to appreciate and difficult to enjoy that demands to be seen on the biggest possible screen by every film lover. Stanley Kubrick went into production on 2001 as one of the great and unpredictable filmmakers of his era and emerged a reclusive master of the art form. He’d made seven movies from 1953-1964 ranging from a philosophical war film (Paths Of Glory) to a comedy of sexual obsession (Lolita) to a satire about the nuclear apocalypse (Dr. Strangelove). Though each project featured his carefully controlled and hermetically sealed photographic style, there was a far looser feel to the films that would follow. For example, Strangelove and Lolita featured a great deal of improvised comedy from Peter Sellers that gave the films a sense of spontaneity, which would subsequently disappear from Kubrick’s work. Essentially given a blank cheque and total creative freedom for 2001 from MGM, the director disappeared to England and spent years in production, carefully labouring over each shot. This led to extraordinary special effects that vividly created space travel for a mesmerized audience and allowed Kubrick to reach a level of technical perfection that he would strive to recreate on every subsequent production. The creative freedom and satisfaction offered by 2001 created a filmmaker willing to shoot 70 takes of a man walking across the street until he got it just right. It gave the later works a cold, detached style that alienated many of Kubrick’s detractors, but given the extraordinary results that sprang from the perfectionism evidenced in 2001, it’s easy to see why the director chased that dragon for the rest of his career. Though co-screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke may have written a novel based on 2001 during production, the film is an almost purely cinematic experience. The story is told entirely through images and sound (particularly in how the images interact with the needle drop soundtrack compiled by the director that is now inseparable from the film). Characters are often little more than a focal point for the cinematography, while dialogue is merely part of the sound design. The film is as much a sensory experience as it is a work of narrative fiction, thrusting audiences into an intensely researched and carefully created world of space travel that in 1968 predicted countless technological leaps from supercomputers to video conferencing and even tablets, all with eerie accuracy. The extraordinary design and groundbreaking model-based special effects (executed so flawlessly that they still feel more real than current CGI creations, even if they are more limited in movement and action) are impressive enough to make the 44-year-old film worth experiencing, but fortunately this is more than just a technical exercise. Kubrick was equally interested in exploring the philosophical implications of space travel, technology, and extraterrestrial encounters as he was in realistically depicting them. The film is rich with ideas and theories that slip into your consciousness as you take in the spectacle. It’s why the movie proved to be a hit during release, as intellectuals and hippies could pontificate for hours about what it might mean while chain smoking their legal or illegal substance of choice. It’s impossible to boil down a movie like 2001 to a simple plot summary, meaning or message, but I think the most compelling theory lies in Kubrick’s lifelong fascination with the concept that any alien life form capable of mastering intergalactic space travel probably evolved beyond a state of existence even comprehendible to humans. With that in mind, the infamous monoliths represent an alien race that gives humanity the higher intelligence of tool making (which they promptly use to harm each other). They then send a signal out through a second monolith when humans finally populate the moon, which subsequently creates a third monolith at Jupiter that a lonely astronaut visits (following a deadly encounter with the computer HAL, reiterating man’s troubled relationship with technology). The astronaut is then transported across space to evolve to the next level of existence to be reborn as the Star Child.

Or at least that’s what it means to me. Maybe the monoliths come from a divine hand or maybe the futuristic vision is just a dream of one of the unevolved monkey-men from the prologue. Regardless, 2001 is a special movie to be cherished. It’s an unforgettable audio/visual experience that could exist only in cinema and one of those special works of art that strives to sort out what it all means without feeling like the pretentious and self-involved musings of a perpetual grad student. If you have even a passing interest in film and have never seen 2001, you owe it to yourself to experience Kubrick’s vision at least once, if only to finally understand a few dozen brilliant Simpsons jokes that have flown over your head for far too long.

2001: A Space Odyssey will screen in 70mm at The Bell Lightbox on Tuesday January 3, 2012 at 8 pm. Phil Brown writes about classic films for Toronto Standard‘s Essential Cinema column.