Hollywood is filled with legends that probably aren’t true, but are so good that it’s best to ignore any nagging doubts. One of the best is a tale of an exhausted Steven Spielberg visiting John Williams after the notoriously disastrous Jaws shoot. He told Williams he didn’t have a shark and needed the music to deliver the threat. The composer calmly put a couple fingers on his piano and played the iconic theme. Spielberg laughed, thinking it was a joke, and when told otherwise he sulked away, convinced that his career was over at 28. Things didn’t quite turn out that way.

It’s funny how even the people involved with a movie sometimes don’t know what they’ve got. Until the first test screening when an audience member ran out of the theater mid-shark-attack to vomit all over the floor and promptly ran back to his seat so he didn’t miss a second of the movie, everyone involved with Jawsthought they were part of one of the biggest disasters of the ‘70s. It ended up becoming the highest-grossing film of all time (well, until George Lucas started playing around with model spaceships) and permanently changed the way Hollywood makes and markets movies. All that success and yet no one could get the damn shark to work until it became a theme park ride. Who knew?

It’s a story so simple most people probably know it before seeing the movie. Once upon a time there was a small and peaceful beach community called Amity. One night a girl disappeared in the water during a good old fashioned ‘70s bonfire. Her body was found mangled. Shark. Big shark. The water-fearing chief says, “shut down the beaches.” The money-loving mayor says, “no.” People keep swimming. Guess who comes back? A grizzled captain says he’ll find him for three, kill him for ten. Too much money. A marine biologist offers help. No one listens. Tourist season comes. Shark buffet.

Finally the chief, the captain, and the marine biologist pile into a rusty boat for some male bonding and shark killing. Adapted from a good, if trashy bestseller by Peter Benchley, the story is about as simple as it gets, tapping into a universal and primal fear of creatures in the water with nasty pointy teeth. That’s kind of simplicity you need in a movie to capture the imagination of, you know, everyone. Doesn’t make it easy to pull off, though, and lord knows making this picture was no day at the beach.

Steven Spielberg signed onto Jaws long before he was a studio-owning mogul who should shake hits off of his head like dandruff from a hippie. He was just a young director who made the leap to features after his rather amazing truck chase TV movie Duel was so well received it got bumped to the big screen, and then so impressed Universal producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown with his official big screen debut The Sugarland Express (a deeply underrated “lovers on the run” yarn and one of Senor Spielbergo’s few flops) that they hired him to adapt that killer fish book they just bought.

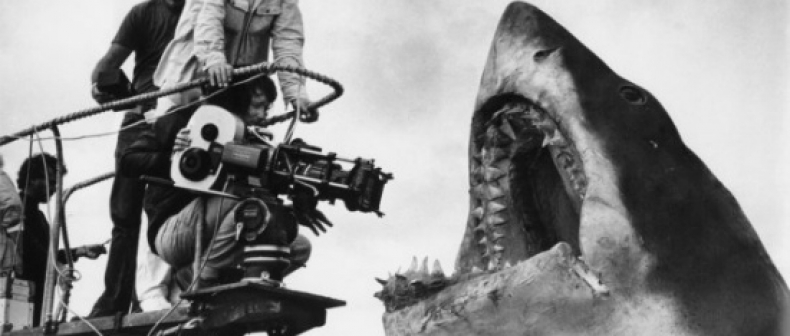

In hindsight it was an ingenious move on the producers’ part, because little did they know they’d found the ultimate audience manipulator, capable of stringing suspense like Hitchcock and sucking out tears like Capra. From there everything went wrong. The script was rewritten constantly. The three leads, Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, and Robert Shaw, were 3rd and 4th choices. The expensive robotic sharks never worked. The boat sunk. Spielberg’s insistence of shooting out on the water with empty horizons was so problematic that days would go by with only a single shot captured. The budget doubled. The shooting schedule never stopped expanding.

Yet, amidst the chaos, Spielberg got creative. He started coming up with inventive ways to shoot around the shark. He, the actors, and the screenwriter would meet for powwows on failed shooting days to rework the script and expand the characters. Suddenly the actors had actual roles to play, the script was sheared down and reworked so many times that it flowed like wine, and Spielberg unintentionally learned that the suggestion of a shark was far more effective than rubber-tooth close-ups. The film became a rollercoaster entertainment factory that starts as a horror film, ends as an action-adventure, and in between fleshes out a whole community of memorable and relatable characters who you actually don’t want to become shark food. How much of that would be true if the production had gone as planned is difficult to say, but the movie certainly wouldn’t be the same. Given what a perfectly crafted entertainment Jaws is, it’s hard to imagine the thing could possibly work any better.

Now, much has been made of the fact that the tremendous success of Jaws killed off the personal filmmaking of the early ‘70s, and rightly so. The thing is that the movie’s layered characterizations, commitment to realism, and loose semi-improvised acting style are deeply influenced by the New Hollywood art films it eclipsed. If you want to intellectualize the material, it’s easy enough to wax on about the dirty capitalist side of America on display, the ‘70s nihilism of an idealized town torn apart by random violence (on the 4th of July no less), the subtext of a beaten man rediscovering his masculinity, etc. That’s all there, but the difference between Jaws and the rest of the early ‘70s Hollywood crop comes down to Roger Corman.

Okay, so Corman wasn’t involved in the production, but the movie follows his famous ‘70s exploitation movie formula to a T: have a big action or violence set piece every 10-15 minutes, cast interesting actors in every role, throw in a little nudity (via some nighttime sideboob in the opening scene), add some comedy, keep the pace pumping at all times, and release the movie as widely as possible rather than building hype in major markets first (something Hollywood never did at the time).

Jaws followed every filmmaking lesson Roger Corman devised and proved that the studios could execute his techniques slicker and better. After Star Wars repeated the trick two years later, the studios have been doing it ever since, while Corman has sadly been shifted to the direct-to-DVD despots making Sharktopus (although not before making a mint off of his 1979 Jaws knock off Piranha). It’s a shame that happened, yet it never would have if the first true Hollywood exploitation movie wasn’t a masterpiece. If I had choose between a world in which Bret Ratner can become one of Hollywood’s most successful directors or a world without Jaws, it’s an easy choice. I do wish that I could also somehow feed Ratner to Jaws, but sadly that’s just crazy talk.

Jaws will screen at the TIFF Bell Lightbox from June 29 to July 4, at 1:30 pm and 7 pm.

____

Phil Brown writes about film for Toronto Standard.

For more, follow us on Twitter at @TorontoStandard and subscribe to our newsletter.